I am committed to making my research accessible and love sharing my experiences in a range of contexts. I have given lectures on varied aspects of visual and material culture to audiences ranging from undergraduate and Masters students in university and art college settings, to local history societies and members of the public at events such as Manchester Histories Festival.

I was invited to speak at the opening of an exhibition of artwork by children from Cambridgeshire schools at Cambridgeshire Music in Histon, organised by ArtBytes. The exhibition was displayed alongside some of the remaining artworks from the Cambridgeshire Collection of Original Artworks for Children, which was developed by Cambridgeshire Director of Education Henry Morris and painter Nan Youngman in the 1940s to lend artworks to schools in the city (and later the county) and acquired hundreds of artworks over the decades, before largely being auctioned in 2017.

I talked about Nan Youngman’s work as an artist, teacher and art adviser for Cambridgeshire, travelling around the county’s rural schools and encouraging the provision of original artworks in schools so children could see real works of art close-up. I explained to an audience of schoolchildren and parents how she wanted children to regard art as part of their everyday lives and environments, to see being an artist as a ‘real’ job they could aspire to, and develop their skills of discussion and critique.

This invited lecture at Salford Museum and Art Gallery for the Friends of Salford Museums explored Salford as a site for the commissioning of public art. Asking ‘what is sculpture’, ‘what form does it take’ and ‘how did it end up there?’, my talk explored works of art in a range of media, from concrete to fibreglass to more conventional materials such as bronze – and some that don’t take the form of an object at all!

The talk started and ended at the University of Salford, exploring the role of the university as art patron and identifying some of the motivations for commissioning public sculpture in the city. This has included contributing to a sense of place and identity and imbuing an atmosphere of newness and modernity.

Covering key eras in public art commissioning, my lecture began in the post-war period with William Mitchell’s landmark ‘Minute Men’, a trio of concrete sculptures unveiled outside the then Salford Technical College in 1966. I then discussed two other key public sculptures for educational settings, created by Alan Boyson and Gertrude Hermes for newly built secondary schools, highlighting issues around care, ownership and conservation, and exploring changing attitudes to public sculpture and its function.

The lecture then considered the long-distance Irwell Sculpture Trail, asking how sculpture can acknowledge and accommodate processes of change and transformation, before turning to the contribution of Salford’s contemporary artist community to the cityscape. This has included recent and ephemeral projects initiated by artists and curators as interventions into their immediate surroundings, drawing attention to issues around gentrification, inclusion and reuse of space.

My talk concluded by returning to Salford University to visit Jai Redman’s interactive fibreglass sculpture ‘Engels’ Beard’ (2016), and a recent highlight of contemporary art in Salford, ‘The Storm Cone’ (2021), an augmented reality experience by Laura Daly and Lucy Pankhurst designed to be experienced via mobile device in Peel Park.

The talk was repeated for Eccles & District History Society in April 2024.

To mark the advent of a new, environmentally friendly white poppy designed by the East London-based worker co-operative Calverts, I was invited by Birmingham Co-operative History Society to talk about the white poppy’s roots in the 1930s peace campaigning of the Co-operative Women’s Guild, alongside Siôn Whellens of Calverts.

I contextualised the white poppy within the Guild’s interwar pacifism and internationalism, exploring the ways in which peace campaigning was a controversial and divisive topic both within the Guild and within the wider women’s movement – as is the wearing of a white poppy today.

Siôn Whellens discussed the links between the worker co-operative and alternative press movements of the 1970s, the women’s movement and the peace movement, and then explained how the new white poppy design (distributed by the Peace Pledge Union) came about in the light of a huge surge in demand in recent years, before outlining the new process of manufacture.

We then took part in a question and answer session encompassing the co-operative movement’s position on peace and pacifism today, in the context of the war in Ukraine, and an ongoing commitment to international co-operation across borders.

I was also in conversation with Mike Wistow from the UK Society for Co-operative Studies (UKSCS) on Zoom in November 2024, discussing the Guild's pacifism and promotion of the white poppy.

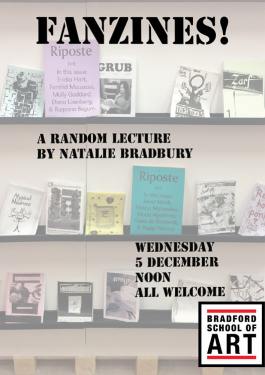

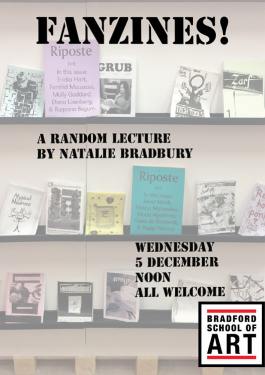

I gave a personal perspective on fanzines as part of Bradford School of Art’s ‘Random Lecture’ series, drawing on material from my own collection of fanzines and printed ephemera, and my experiences of publishing The Shrieking Violet.

I discussed the different forms fanzines have taken, in terms of style and content, and their ongoing evolution. Fanzines are often associated with small, rough-and-ready, self-published magazines aimed at special interest communities such as football supporters, music fans, vegans and anarchists. My lecture expanded this to consider a range of other examples of the genre, from hyperlocal examinations of cities and neighbourhoods, and city critiques, to publications that showcase the work of artists, photographers and poets, to sleek, well-designed objects that hold much in common with artists’ books. I discussed the ways in which the aesthetics and practice of self-publishing has been ‘mainstreamed’, and the co-option and collecting of fanzines by institutions such as universities and art galleries.

I concluded by looking at the fanzine in the age of the internet, and the ways in which the internet supports fanzine-making by creating communities and increased opportunities for the distribution and consumption of self-published material.

I was invited to lead a writing workshop for students on the Projects and Places pathway of the Fine Art Masters at the University of Central Lancashire, showing the different types of writing I have done, many of which share an interest in place, and the different forms and approaches I have used, from self-publishing fanzines to collaborations, research projects and public events.

I took along lots of examples of publications which have inspired me, and we discussed what makes us hold on to or keep a publication in a world where we’re surrounded by printed matter and information.

What effect does good writing have on us – does it make us want to learn and research more, or go out and visit an exhibition or place?

We also discussed the form and function of art writing. How and where can you be critical, and who has the space to be critical? What is the role of conversation and dialogue in criticism?

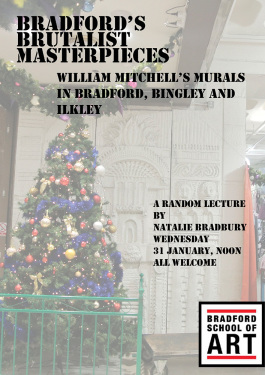

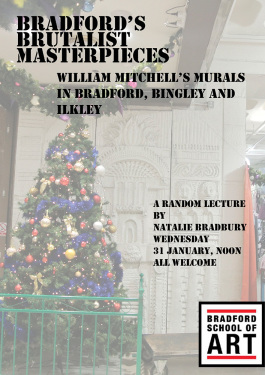

A guest lecture as part of the ‘Random Lecture series’ at Bradford School of Art.

Born in 1925, the artist and industrial designer William Mitchell’s work can be seen in towns and cities around the world. However, it does not hang on the wall of art galleries, but is an integral part of the buildings in which it is found. These range from everyday places such as schools, libraries, pubs, subway underpasses and the foyers of post-war towerblocks, to flagship buildings like Harrods and the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King in Liverpool.

My talk gave an overview of Mitchell’s work and career, focusing in particular on three artworks by William Mitchell in the Bradford area which demonstrate his post-war work in municipal and civic contexts as well as for corporate and commercial clients.

Using innovative techniques and working in media such as moulded concrete and fibreglass, all three murals are distinctively of Mitchell’s style, yet take different stylistic approaches, from abstracted pattern-making to more representational imagery incorporating elements of the history of the area in which they are located. My lecture explored a series of concrete reliefs in Bradford’s Kirkgate market, built in 1973 to replace a previous Victorian market, undertaken by Mitchell or one of his associates; thirteen fibreglass relief panels, commissioned for the former Bradford and Bingley Building Society headquarters in Bingley in the early 1970s and depicting the architectural and engineering landmarks of the area; and a large relief for the Ilkley Wool Secretariat, completed in 1968, which explores the history of wool manufacture locally.

I used these case studies to highlight wider changes in attitudes towards post-war architecture, and the ways in which these types of artworks are regarded: whilst a new home has been sought in recent years for the Bingley reliefs, which were removed as the highly unpopular building in which they were situated was demolished, Mitchell’s Ilkley work has been widely feted and was celebrated with Grade II listing by Historic England in 2015.

A guest lecture as part of the ‘Random Lecture series’ at Bradford School of Art.

Like many institutions, universities and colleges often publicly display portraits of grandees such as chancellors and vice-chancellors in order to convey a sense of tradition, heritage and prestige. Less common but more interesting are those further and higher education establishments which have sought to display works of modern art around campus, turning the educational environment into a gallery space. Universities that have chosen to collect and display contemporary art range from modern, post-war universities, where brutalist 1960s architecture is offset by landscaped grounds filled with sculpture by artists such as Henry Moore, to redbrick Victorian universities, to former technical colleges which attained university status in the 1960s. Here (primarily) paintings were purchased for display in communal areas such as corridors and lecture rooms, as well as more privately in staff offices. Between the 1940s and the 1960s, many teacher training colleges also became enthusiastic buyers of contemporary art as part of a broader culture of artistic patronage among educational establishments such as schools, and art became a part of the training context for a future generation of educators.

Some educational establishments continue to take pride in these collections, make a point of promoting public awareness and access, and continue to actively acquire work. In other cases artworks have been lost, faded into the background or become hidden in the everyday fabric of the institution as universities and colleges have merged, been expanded, modernised and redeveloped over time. This has been due to insufficient documentation and knowledge about the optimum conditions for the display of artworks, a lack of dedicated resource and staff time, or a lack of planning around care and maintenance for the future.

My lecture explored the historical establishment and development of some of these educational art collections in colleges and universities in the twentieth century. I explored their perceived educational impact and appeal, the types of artworks that were considered to be of value and use for display in educational settings, and what this says about changing ideas about the nature and purpose of education. I asked what an educational art collection might look like now and what it might add to the educational experience of today’s students.

I was invited to talk about my work and read from The Shrieking Violet as part of Salford Zine Library’s takeover of the Deli Lama Café during the annual Sounds from the Other City music festival, alongside other fanzine-makers and poets. Fanzines from the library were available to explore and browse.

A public talk for the March meeting of the Manchester Centre for Regional History.

Pictures for Schools was a scheme founded in 1947, which aimed to get original works of art into ‘schools of every kind’ so children could grow up with art as part of their everyday environments. Between 1947 and 1969, annual Pictures for Schools exhibitions were held in London (with the exception of 1957, when a venue in London could not be found and the exhibition was instead held at Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery).

Here, contemporary artworks by living British artists were displayed and sold at prices affordable to educational buyers. Contributors ranged from well-known names such as LS Lowry to students who were obscure at the time but later went on to make a name for themselves.

Local education authorities, education committees and museum services across the country made the annual trip from London to make purchases from the scheme, and extensive collections of artworks were built up in towns, cities and counties large and small for loan to schools. Several schools in Manchester benefited from the opportunity to buy work, and education committees in Lancashire, Rochdale and Manchester were among the regular buyers from Pictures for Schools. Another purchaser was Manchester Art Gallery’s Rutherston Loan Collection for educational institutions in the north of England.

However, over the decades schools have closed, changed name or merged, and local authorities have come under pressures such as boundary changes and financial constraints. Many of these collections have now disappeared with little or no acknowledgment that such a service once existed. My talk asked: Does Pictures for Schools have a legacy in Manchester today, and can these artworks still have any relevance in the twentieth-first-century classroom?

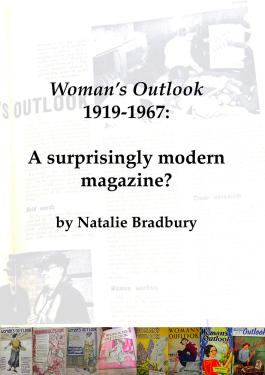

My talk ‘Woman’s Outlook: a surprisingly modern magazine?’, devised at the invitation of Rochdale Pioneers Museum, was the culmination of several days of research into the twentieth century co-operative women’s journal Woman’s Outlook in the National Co-operative Archive in Manchester. I created a new publication to present the history, style and impact of the magazine, combining images and information from Woman’s Outlook with interviews with two members of campaigning organisation the Co-operative Women’s Guild, past and present.

For nearly five decades, Woman’s Outlook was the voice of the Co-operative Women’s Guild, providing an enticing mixture of articles addressing both the personal and the political, combining fashion, fiction, features and recipes with advice for working women. The talk ‘Woman’s Outlook: a surprisingly modern magazine?’ explored some of the key issues addressed in Outlook, including women’s representation in parliament, maternity services and family planning and equal pay.

My talk concluded by comparing the subject matter of Woman’s Outlook with that of a current-day women’s magazine, Stylist, from reader surveys aimed at building up a picture of what it’s like to be a modern women, to highlighting issues like abortion, equal pay, women’s continued underrepresentation in Parliament, childcare and flexible working.

The talk ‘Woman’s Outlook: a surprisingly modern magazine?’ was repeated at the Working Class Movement Library in Salford in May 2013, as part of its Invisible Histories series. In March 2014, I was invited to deliver the talk at the People’s History Museum in Manchester to accompany the exhibition The People’s Business – 150 Years of the Co-operative. This took place during Manchester Histories Festival as part of a series of events celebrating Manchester’s radical women, themed ‘Wonder Women’. I was invited to give the talk to a public audience at Cafe Kino, a co-operatively run cafe in Bristol, in June 2014. The talk was also repeated for the Social Lites Women’s Institute branch in Flixton, Urmston in September 2014, and at Bradford School of Art as part of its Random Lecture series in October 2018.

In April 2013 I was invited to deliver a guest-lecture on my experiences publishing The Shrieking Violet for a group of undergraduate art, design and art history students on Manchester School of Art’s interdisciplinary Unit X course as part of their project to create fanzines and organise a fanzine fair. My talk encompassed the process of design and layout, gathering content and working with writers and illustrators, and publicity, networking and distribution. I also discussed The Shrieking Violet as part of a wider context of publications from the punk era, as well as a range of specialist media from vegan and anarchist fanzines to literary, design and artist-created fanzines.

In May 2013, I repeated the talk for a public audience at a pop-up shop on Market Street, Bradford. Taking place during the Bradford Baked Zines festival, a week-long celebration of self-publishing and DIY culture, it was followed by a question and answer session.

I am committed to making my research accessible and love sharing my experiences in a range of contexts. I have given lectures on varied aspects of visual and material culture to audiences ranging from undergraduate and Masters students in university and art college settings, to local history societies and members of the public at events such as Manchester Histories Festival.

I was invited to speak at the opening of an exhibition of artwork by children from Cambridgeshire schools at Cambridgeshire Music in Histon, organised by ArtBytes. The exhibition was displayed alongside some of the remaining artworks from the Cambridgeshire Collection of Original Artworks for Children, which was developed by Cambridgeshire Director of Education Henry Morris and painter Nan Youngman in the 1940s to lend artworks to schools in the city (and later the county) and acquired hundreds of artworks over the decades, before largely being auctioned in 2017.

I talked about Nan Youngman’s work as an artist, teacher and art adviser for Cambridgeshire, travelling around the county’s rural schools and encouraging the provision of original artworks in schools so children could see real works of art close-up. I explained to an audience of schoolchildren and parents how she wanted children to regard art as part of their everyday lives and environments, to see being an artist as a ‘real’ job they could aspire to, and develop their skills of discussion and critique.

This invited lecture at Salford Museum and Art Gallery for the Friends of Salford Museums explored Salford as a site for the commissioning of public art. Asking ‘what is sculpture’, ‘what form does it take’ and ‘how did it end up there?’, my talk explored works of art in a range of media, from concrete to fibreglass to more conventional materials such as bronze – and some that don’t take the form of an object at all!

The talk started and ended at the University of Salford, exploring the role of the university as art patron and identifying some of the motivations for commissioning public sculpture in the city. This has included contributing to a sense of place and identity and imbuing an atmosphere of newness and modernity.

Covering key eras in public art commissioning, my lecture began in the post-war period with William Mitchell’s landmark ‘Minute Men’, a trio of concrete sculptures unveiled outside the then Salford Technical College in 1966. I then discussed two other key public sculptures for educational settings, created by Alan Boyson and Gertrude Hermes for newly built secondary schools, highlighting issues around care, ownership and conservation, and exploring changing attitudes to public sculpture and its function.

The lecture then considered the long-distance Irwell Sculpture Trail, asking how sculpture can acknowledge and accommodate processes of change and transformation, before turning to the contribution of Salford’s contemporary artist community to the cityscape. This has included recent and ephemeral projects initiated by artists and curators as interventions into their immediate surroundings, drawing attention to issues around gentrification, inclusion and reuse of space.

My talk concluded by returning to Salford University to visit Jai Redman’s interactive fibreglass sculpture ‘Engels’ Beard’ (2016), and a recent highlight of contemporary art in Salford, ‘The Storm Cone’ (2021), an augmented reality experience by Laura Daly and Lucy Pankhurst designed to be experienced via mobile device in Peel Park.

The talk was repeated for Eccles & District History Society in April 2024.

To mark the advent of a new, environmentally friendly white poppy designed by the East London-based worker co-operative Calverts, I was invited by Birmingham Co-operative History Society to talk about the white poppy’s roots in the 1930s peace campaigning of the Co-operative Women’s Guild, alongside Siôn Whellens of Calverts.

I contextualised the white poppy within the Guild’s interwar pacifism and internationalism, exploring the ways in which peace campaigning was a controversial and divisive topic both within the Guild and within the wider women’s movement – as is the wearing of a white poppy today.

Siôn Whellens discussed the links between the worker co-operative and alternative press movements of the 1970s, the women’s movement and the peace movement, and then explained how the new white poppy design (distributed by the Peace Pledge Union) came about in the light of a huge surge in demand in recent years, before outlining the new process of manufacture.

We then took part in a question and answer session encompassing the co-operative movement’s position on peace and pacifism today, in the context of the war in Ukraine, and an ongoing commitment to international co-operation across borders.

I was also in conversation with Mike Wistow from the UK Society for Co-operative Studies (UKSCS) on Zoom in November 2024, discussing the Guild's pacifism and promotion of the white poppy.

I gave a personal perspective on fanzines as part of Bradford School of Art’s ‘Random Lecture’ series, drawing on material from my own collection of fanzines and printed ephemera, and my experiences of publishing The Shrieking Violet.

I discussed the different forms fanzines have taken, in terms of style and content, and their ongoing evolution. Fanzines are often associated with small, rough-and-ready, self-published magazines aimed at special interest communities such as football supporters, music fans, vegans and anarchists. My lecture expanded this to consider a range of other examples of the genre, from hyperlocal examinations of cities and neighbourhoods, and city critiques, to publications that showcase the work of artists, photographers and poets, to sleek, well-designed objects that hold much in common with artists’ books. I discussed the ways in which the aesthetics and practice of self-publishing has been ‘mainstreamed’, and the co-option and collecting of fanzines by institutions such as universities and art galleries.

I concluded by looking at the fanzine in the age of the internet, and the ways in which the internet supports fanzine-making by creating communities and increased opportunities for the distribution and consumption of self-published material.

I was invited to lead a writing workshop for students on the Projects and Places pathway of the Fine Art Masters at the University of Central Lancashire, showing the different types of writing I have done, many of which share an interest in place, and the different forms and approaches I have used, from self-publishing fanzines to collaborations, research projects and public events.

I took along lots of examples of publications which have inspired me, and we discussed what makes us hold on to or keep a publication in a world where we’re surrounded by printed matter and information.

What effect does good writing have on us – does it make us want to learn and research more, or go out and visit an exhibition or place?

We also discussed the form and function of art writing. How and where can you be critical, and who has the space to be critical? What is the role of conversation and dialogue in criticism?

A guest lecture as part of the ‘Random Lecture series’ at Bradford School of Art.

Born in 1925, the artist and industrial designer William Mitchell’s work can be seen in towns and cities around the world. However, it does not hang on the wall of art galleries, but is an integral part of the buildings in which it is found. These range from everyday places such as schools, libraries, pubs, subway underpasses and the foyers of post-war towerblocks, to flagship buildings like Harrods and the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King in Liverpool.

My talk gave an overview of Mitchell’s work and career, focusing in particular on three artworks by William Mitchell in the Bradford area which demonstrate his post-war work in municipal and civic contexts as well as for corporate and commercial clients.

Using innovative techniques and working in media such as moulded concrete and fibreglass, all three murals are distinctively of Mitchell’s style, yet take different stylistic approaches, from abstracted pattern-making to more representational imagery incorporating elements of the history of the area in which they are located. My lecture explored a series of concrete reliefs in Bradford’s Kirkgate market, built in 1973 to replace a previous Victorian market, undertaken by Mitchell or one of his associates; thirteen fibreglass relief panels, commissioned for the former Bradford and Bingley Building Society headquarters in Bingley in the early 1970s and depicting the architectural and engineering landmarks of the area; and a large relief for the Ilkley Wool Secretariat, completed in 1968, which explores the history of wool manufacture locally.

I used these case studies to highlight wider changes in attitudes towards post-war architecture, and the ways in which these types of artworks are regarded: whilst a new home has been sought in recent years for the Bingley reliefs, which were removed as the highly unpopular building in which they were situated was demolished, Mitchell’s Ilkley work has been widely feted and was celebrated with Grade II listing by Historic England in 2015.

A guest lecture as part of the ‘Random Lecture series’ at Bradford School of Art.

Like many institutions, universities and colleges often publicly display portraits of grandees such as chancellors and vice-chancellors in order to convey a sense of tradition, heritage and prestige. Less common but more interesting are those further and higher education establishments which have sought to display works of modern art around campus, turning the educational environment into a gallery space. Universities that have chosen to collect and display contemporary art range from modern, post-war universities, where brutalist 1960s architecture is offset by landscaped grounds filled with sculpture by artists such as Henry Moore, to redbrick Victorian universities, to former technical colleges which attained university status in the 1960s. Here (primarily) paintings were purchased for display in communal areas such as corridors and lecture rooms, as well as more privately in staff offices. Between the 1940s and the 1960s, many teacher training colleges also became enthusiastic buyers of contemporary art as part of a broader culture of artistic patronage among educational establishments such as schools, and art became a part of the training context for a future generation of educators.

Some educational establishments continue to take pride in these collections, make a point of promoting public awareness and access, and continue to actively acquire work. In other cases artworks have been lost, faded into the background or become hidden in the everyday fabric of the institution as universities and colleges have merged, been expanded, modernised and redeveloped over time. This has been due to insufficient documentation and knowledge about the optimum conditions for the display of artworks, a lack of dedicated resource and staff time, or a lack of planning around care and maintenance for the future.

My lecture explored the historical establishment and development of some of these educational art collections in colleges and universities in the twentieth century. I explored their perceived educational impact and appeal, the types of artworks that were considered to be of value and use for display in educational settings, and what this says about changing ideas about the nature and purpose of education. I asked what an educational art collection might look like now and what it might add to the educational experience of today’s students.

I was invited to talk about my work and read from The Shrieking Violet as part of Salford Zine Library’s takeover of the Deli Lama Café during the annual Sounds from the Other City music festival, alongside other fanzine-makers and poets. Fanzines from the library were available to explore and browse.

A public talk for the March meeting of the Manchester Centre for Regional History.

Pictures for Schools was a scheme founded in 1947, which aimed to get original works of art into ‘schools of every kind’ so children could grow up with art as part of their everyday environments. Between 1947 and 1969, annual Pictures for Schools exhibitions were held in London (with the exception of 1957, when a venue in London could not be found and the exhibition was instead held at Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery).

Here, contemporary artworks by living British artists were displayed and sold at prices affordable to educational buyers. Contributors ranged from well-known names such as LS Lowry to students who were obscure at the time but later went on to make a name for themselves.

Local education authorities, education committees and museum services across the country made the annual trip from London to make purchases from the scheme, and extensive collections of artworks were built up in towns, cities and counties large and small for loan to schools. Several schools in Manchester benefited from the opportunity to buy work, and education committees in Lancashire, Rochdale and Manchester were among the regular buyers from Pictures for Schools. Another purchaser was Manchester Art Gallery’s Rutherston Loan Collection for educational institutions in the north of England.

However, over the decades schools have closed, changed name or merged, and local authorities have come under pressures such as boundary changes and financial constraints. Many of these collections have now disappeared with little or no acknowledgment that such a service once existed. My talk asked: Does Pictures for Schools have a legacy in Manchester today, and can these artworks still have any relevance in the twentieth-first-century classroom?

My talk ‘Woman’s Outlook: a surprisingly modern magazine?’, devised at the invitation of Rochdale Pioneers Museum, was the culmination of several days of research into the twentieth century co-operative women’s journal Woman’s Outlook in the National Co-operative Archive in Manchester. I created a new publication to present the history, style and impact of the magazine, combining images and information from Woman’s Outlook with interviews with two members of campaigning organisation the Co-operative Women’s Guild, past and present.

For nearly five decades, Woman’s Outlook was the voice of the Co-operative Women’s Guild, providing an enticing mixture of articles addressing both the personal and the political, combining fashion, fiction, features and recipes with advice for working women. The talk ‘Woman’s Outlook: a surprisingly modern magazine?’ explored some of the key issues addressed in Outlook, including women’s representation in parliament, maternity services and family planning and equal pay.

My talk concluded by comparing the subject matter of Woman’s Outlook with that of a current-day women’s magazine, Stylist, from reader surveys aimed at building up a picture of what it’s like to be a modern women, to highlighting issues like abortion, equal pay, women’s continued underrepresentation in Parliament, childcare and flexible working.

The talk ‘Woman’s Outlook: a surprisingly modern magazine?’ was repeated at the Working Class Movement Library in Salford in May 2013, as part of its Invisible Histories series. In March 2014, I was invited to deliver the talk at the People’s History Museum in Manchester to accompany the exhibition The People’s Business – 150 Years of the Co-operative. This took place during Manchester Histories Festival as part of a series of events celebrating Manchester’s radical women, themed ‘Wonder Women’. I was invited to give the talk to a public audience at Cafe Kino, a co-operatively run cafe in Bristol, in June 2014. The talk was also repeated for the Social Lites Women’s Institute branch in Flixton, Urmston in September 2014, and at Bradford School of Art as part of its Random Lecture series in October 2018.

In April 2013 I was invited to deliver a guest-lecture on my experiences publishing The Shrieking Violet for a group of undergraduate art, design and art history students on Manchester School of Art’s interdisciplinary Unit X course as part of their project to create fanzines and organise a fanzine fair. My talk encompassed the process of design and layout, gathering content and working with writers and illustrators, and publicity, networking and distribution. I also discussed The Shrieking Violet as part of a wider context of publications from the punk era, as well as a range of specialist media from vegan and anarchist fanzines to literary, design and artist-created fanzines.

In May 2013, I repeated the talk for a public audience at a pop-up shop on Market Street, Bradford. Taking place during the Bradford Baked Zines festival, a week-long celebration of self-publishing and DIY culture, it was followed by a question and answer session.