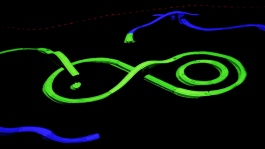

Sam Meech, Concrete Connexions (2017), courtesy of Signal Film & Media

When our civilisation falls, what will we leave for future civilisations – and will they understand, or will they project their own meanings and interpretations?

This question forms one of the central concerns of Sam Meech’s exhibition Time Back Way Back, which takes its inspiration from the 1980 science-fiction book Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban. Riddley Walker explores the world 2,000 years after a nuclear apocalypse; a scenario which feels both timely and resonant in Barrow, the landscape and economy of which is defined by the defence industry. Nuclear submarines are built by BAE systems in the town and, as Meech points out; “if the end of the world comes, something in it will say ‘made in Barrow’.”

In ‘Oh What We Ben! And What We Come To!’ Meech presents us with a kind of ‘concrete Pompeii’, which the audience is invited to navigate in near-darkness, using a torch. The floor is littered with leaves cast in concrete, giving a permanence to that which is usually ephemeral. The disposable becomes solidified. ‘Girt Shyning Weal’ invites us to become archaeologists of the present, taking a hammer to a concrete block in order to unearth ‘fidget spinners’; today’s consumer goods become tomorrow’s cultural artefact.

The exhibition also draws on the history of Barrow, referencing the now-defunct stations and miles of railway track that once transported commodities such as iron ore around the area. Although Meech is based in Manchester, he worked with local people interested in digital art in the period leading up the exhibition, and much of the work is interactive and responsive. ‘Concrete Connexions’ asks the visitor to use a laser pen to follow the routes of a modular Brio set that twists around the floor in loops without ever reaching a destination. The tiny train lines glow with coloured lights, triggered by a laser which pulsates gently like the outline of a city viewed from a distance.

Meech combines analogue and digital technology to disorienting effect. At Barrow station, ‘Viddyo Station’ plays archival footage of the town on a large screen in the foyer. Digitally translated, the images are disrupted, appearing to take on the glitches and constantly shifting information of a digital sign.

An unsettling combination of electronic and found sounds adds to the eeriness, including the high-pitched refrain of ‘Such a Noys’ – a recording of a performance of a choir of local children at the station. Like much of the work, the words are drawn from Riddley Walker, which is written in language which is both familiar and strange, based on a phonetic translation of a Kentish dialect. Narrated by a young boy, the book presents a society whose language, traditions and culture are based on the fragments left by previous civilisations, leading to mistranslations and misunderstandings.

Meech draws on this to great effect in Time Back Way Back. Each work is accompanied by a text written in the language of Riddley Walker. Rather than explaining or describing, it both illuminates and obfuscates what we see in front of us.

Originally published in Corridor8, December 2017

Sam Meech, Concrete Connexions (2017), courtesy of Signal Film & Media

When our civilisation falls, what will we leave for future civilisations – and will they understand, or will they project their own meanings and interpretations?

This question forms one of the central concerns of Sam Meech’s exhibition Time Back Way Back, which takes its inspiration from the 1980 science-fiction book Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban. Riddley Walker explores the world 2,000 years after a nuclear apocalypse; a scenario which feels both timely and resonant in Barrow, the landscape and economy of which is defined by the defence industry. Nuclear submarines are built by BAE systems in the town and, as Meech points out; “if the end of the world comes, something in it will say ‘made in Barrow’.”

In ‘Oh What We Ben! And What We Come To!’ Meech presents us with a kind of ‘concrete Pompeii’, which the audience is invited to navigate in near-darkness, using a torch. The floor is littered with leaves cast in concrete, giving a permanence to that which is usually ephemeral. The disposable becomes solidified. ‘Girt Shyning Weal’ invites us to become archaeologists of the present, taking a hammer to a concrete block in order to unearth ‘fidget spinners’; today’s consumer goods become tomorrow’s cultural artefact.

The exhibition also draws on the history of Barrow, referencing the now-defunct stations and miles of railway track that once transported commodities such as iron ore around the area. Although Meech is based in Manchester, he worked with local people interested in digital art in the period leading up the exhibition, and much of the work is interactive and responsive. ‘Concrete Connexions’ asks the visitor to use a laser pen to follow the routes of a modular Brio set that twists around the floor in loops without ever reaching a destination. The tiny train lines glow with coloured lights, triggered by a laser which pulsates gently like the outline of a city viewed from a distance.

Meech combines analogue and digital technology to disorienting effect. At Barrow station, ‘Viddyo Station’ plays archival footage of the town on a large screen in the foyer. Digitally translated, the images are disrupted, appearing to take on the glitches and constantly shifting information of a digital sign.

An unsettling combination of electronic and found sounds adds to the eeriness, including the high-pitched refrain of ‘Such a Noys’ – a recording of a performance of a choir of local children at the station. Like much of the work, the words are drawn from Riddley Walker, which is written in language which is both familiar and strange, based on a phonetic translation of a Kentish dialect. Narrated by a young boy, the book presents a society whose language, traditions and culture are based on the fragments left by previous civilisations, leading to mistranslations and misunderstandings.

Meech draws on this to great effect in Time Back Way Back. Each work is accompanied by a text written in the language of Riddley Walker. Rather than explaining or describing, it both illuminates and obfuscates what we see in front of us.

Originally published in Corridor8, December 2017

⬑

⬑