‘A Requiem for Preston Bus Station’, performed by Noizechoir and Bruce Rafeek at Preston Bus Station as part of They Eat Culture’s event Journey to the End of the World (2013), words by Bruce Rafeek

Founded by Lindsay Duncanson and Marek Gabrysch in 2011, Noizechoir is an experimental choir based in Newcastle which explores landscape, science and nature through playful and inventive uses of the voice.

Its performances take inspiration from the specificity of places, from the grand and spectacular to the eerie and the mundane, both in the UK and internationally. Sometimes these works are commissioned, other times they arise from members’ own interests in places or preoccupations with particular geographical phenomena. From her studio over Zoom, Duncan ran me through a list of venues that the choir has responded to and performed in over the past nine years. Highlights have included a dank, smelly space underneath the library at Newcastle Civic Centre; the former jail cells of Middlesbrough Town Hall; solemn, oak-lined Redhills Miners Hall in Durham, where each colliery once had its own seat; Preston Bus Station, a 1960s Brutalist landmark recently threatened with demolition but now celebrated as an icon of modernist architecture; and Lindisfarne in the far North East, where atmospheric Holy Island is cut off from the mainland by a tidal causeway.

“The Miners Hall looks like a Methodist church. The score honours the space and the history of mining in County Durham. It goes down several layers to the depths of the earth and through different tones and pitches, starting in the air and coming back out again.”: ‘Breath in (g) old air’, performed by Noizechoir at Redhills: Durham Miners Hall as part of DJazz: the Durham City Jazz Festival (2019)

The creation of each new piece involves research and immersion in a place, which is workshopped collaboratively by members of the choir before being visualised as a ‘graphic score’. Drawn primarily by the choir’s directors in watercolour and ink, these scores are not just instructions for performance but works of art in their own right.

Whereas traditional musical notation uses accepted conventions such as keys and tempos, and the shape and placement of a note on a stave to indicate its pitch and duration, graphic scores emerged in the 1950s as an alternative way of visualising compositions. Used by experimental composers such as John Cage, Cornelius Cardew and Pauline Oliveros, graphic scores allow for a freer interpretation by the reader or performer at the same time as enabling the incorporation of sounds such as speech and incidental noises. Whilst some retain elements of traditional musical notation, others appear more like visual stories or cartoon strips, which can be read even by those not trained in classical music.

Noizechoir’s graphic scores enable them to capture the feeling of a piece of music. Some scores replicate the shape of sounds: they might show the shape the mouth should make and the sound being aimed for, or indicate the length of a breath. Others paint ideas about a place.

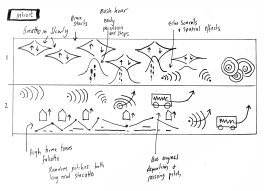

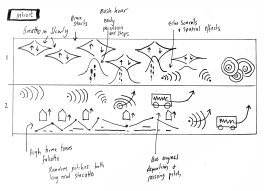

“We copied the sound of buses, diesel engines and people running across the bus station, asking ‘how do you do that with your mouth and without using reverb?’”: A Requiem for Preston Bus Station’, drawn by Marek Gabrysch, featuring the poet Bruce Rafeek, performed by Noizechoir and Bruce Rafeek at Preston Bus Station as part of They Eat Culture’s event Journey to the End of the World (2013)

After the score is drawn out and printed, objects and photos may be added on top and the score reprinted to include these additions. Each chorister then annotates their own copy of the score, building a collection of individual interpretations.

Noizechoir is drawn from a regular group of eight to fourteen members, who range from artists, musicians and singing tutors to doctors, dentists and psychiatrists. Duncanson describes the choir’s temperament as “anarchic,” and it’s clear that the choir provides a social space and a shared sense of fun as well as an interest in experimenting with sound. Although some members read music, and several are former cassock-wearing church choristers, the graphic scores provide an inclusive way of bringing this disparate group of performers together. Graphic scores also make sound-making tangible, explains Duncanson: they provide “something you can put your hands on and say ‘this is what we did’.”

Looking at Noizechoir’s graphic scores and listening to their recordings has taken me on a journey round northern England. Preston Bus Station is a place I’ve visited several times, in a town I know reasonably well. The following score was performed alongside a poem by Bruce Rafeek which evokes the history of the building, the spirit in which it was built and its place in the identity of the town. Together, they captured my imagination and made me want to revisit this seemingly ordinary place.

“We used the architecture as a score.”: ‘A Requiem for Preston Bus Station’, drawn by Marek Gabrysch, featuring the poet Bruce Rafeek, performed by Noizechoir and Bruce Rafeek at Preston Bus Station as part of They Eat Culture’s event Journey to the End of the World (2013)

Engines hiss. Buses reverse with insistent warning beeps. Doors open, half-close and open again. Footsteps run across the building and luggage drags across the rubber floor. Echoes. People bustle; confusion clangs in the distance, somewhere someone shouts and calls. Overlapping voices suggest multiple purposes: counter sales and travel advice vie with intrusive phone calls, tittle-tattle and the depersonalised, automated voice of the self-service supermarket checkout.

Preston, Poulton, Blackpool via Kirkham, Fleetwood, Ormskirk, Leyland, the Lakes. The destination announcements suggest home time, visits to family and friends or a day trip to the mountains or the sea.

It’s a familiar – if tired – place. This is the backdrop for hours spent hanging around waiting, worrying about delays and missed connections. But there’s also life and excitement here. It might have been built in a different era, but still the bus station has an essential function: it connects us with other places and people. It’s a social space.

The bus pulls in. The engine starts. The journey begins.

Lindisfarne is somewhere I have long wanted to visit. I have never managed to make the journey due to its remoteness and geographical distance from the North West, but Noizechoir’s work has made it feel a little bit closer.

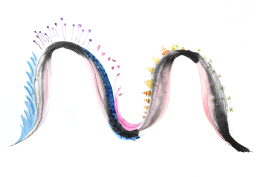

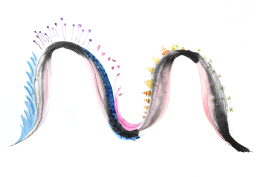

“We researched the tidal patterns and migrating birds of Holy Island and played with the sea, the wind, traffic and people. The dynamics were based on the volume of the tide.”: ‘Tidalisle (Lindisfarne)’, designed by Marek Gabrsych and painted by Lindsay Duncanson, created for Perigrini Lindisfarne and performed by Noizechoir in Lindisfarne bird hide (2017)

The sea sends out feelers like wandering tentacles, then the tide rushes in with a sudden shock before beating a hasty retreat. It swells with a deep, ominous belly roar, a groan and a creak, as if it’s being heaved up from the deep, then ebbs away.

Again and again it comes, faster and more regular now, building up a rhythm as it’s pulled in and out. In the background an incantation is too indistinct to make out.

The waves lap and drag along the shore. Birds sigh and coo overhead. More and more join in, flitting around one another in the sky.

In the distance a bell tolls.

Footsteps, one in front of another. Slowly. A crossing.

The bell continues to call.

The sea retreats, to silence, the sound of the waves replaced by a whistling wind. The tinkling drip-dropping of rain grows more persistent.

Night falls.

The chanting grows, louder and louder, merging with the hiss of the sea. Then it vanishes, fading back until only a soft patter of water remains.

It begins again.

Originally published in the Fourdrinier, September 2020

See more of Noizechoir’s scores and listen to some of their performances

‘A Requiem for Preston Bus Station’, performed by Noizechoir and Bruce Rafeek at Preston Bus Station as part of They Eat Culture’s event Journey to the End of the World (2013), words by Bruce Rafeek

Founded by Lindsay Duncanson and Marek Gabrysch in 2011, Noizechoir is an experimental choir based in Newcastle which explores landscape, science and nature through playful and inventive uses of the voice.

Its performances take inspiration from the specificity of places, from the grand and spectacular to the eerie and the mundane, both in the UK and internationally. Sometimes these works are commissioned, other times they arise from members’ own interests in places or preoccupations with particular geographical phenomena. From her studio over Zoom, Duncan ran me through a list of venues that the choir has responded to and performed in over the past nine years. Highlights have included a dank, smelly space underneath the library at Newcastle Civic Centre; the former jail cells of Middlesbrough Town Hall; solemn, oak-lined Redhills Miners Hall in Durham, where each colliery once had its own seat; Preston Bus Station, a 1960s Brutalist landmark recently threatened with demolition but now celebrated as an icon of modernist architecture; and Lindisfarne in the far North East, where atmospheric Holy Island is cut off from the mainland by a tidal causeway.

“The Miners Hall looks like a Methodist church. The score honours the space and the history of mining in County Durham. It goes down several layers to the depths of the earth and through different tones and pitches, starting in the air and coming back out again.”: ‘Breath in (g) old air’, performed by Noizechoir at Redhills: Durham Miners Hall as part of DJazz: the Durham City Jazz Festival (2019)

The creation of each new piece involves research and immersion in a place, which is workshopped collaboratively by members of the choir before being visualised as a ‘graphic score’. Drawn primarily by the choir’s directors in watercolour and ink, these scores are not just instructions for performance but works of art in their own right.

Whereas traditional musical notation uses accepted conventions such as keys and tempos, and the shape and placement of a note on a stave to indicate its pitch and duration, graphic scores emerged in the 1950s as an alternative way of visualising compositions. Used by experimental composers such as John Cage, Cornelius Cardew and Pauline Oliveros, graphic scores allow for a freer interpretation by the reader or performer at the same time as enabling the incorporation of sounds such as speech and incidental noises. Whilst some retain elements of traditional musical notation, others appear more like visual stories or cartoon strips, which can be read even by those not trained in classical music.

Noizechoir’s graphic scores enable them to capture the feeling of a piece of music. Some scores replicate the shape of sounds: they might show the shape the mouth should make and the sound being aimed for, or indicate the length of a breath. Others paint ideas about a place.

“We copied the sound of buses, diesel engines and people running across the bus station, asking ‘how do you do that with your mouth and without using reverb?’”: A Requiem for Preston Bus Station’, drawn by Marek Gabrysch, featuring the poet Bruce Rafeek, performed by Noizechoir and Bruce Rafeek at Preston Bus Station as part of They Eat Culture’s event Journey to the End of the World (2013)

After the score is drawn out and printed, objects and photos may be added on top and the score reprinted to include these additions. Each chorister then annotates their own copy of the score, building a collection of individual interpretations.

Noizechoir is drawn from a regular group of eight to fourteen members, who range from artists, musicians and singing tutors to doctors, dentists and psychiatrists. Duncanson describes the choir’s temperament as “anarchic,” and it’s clear that the choir provides a social space and a shared sense of fun as well as an interest in experimenting with sound. Although some members read music, and several are former cassock-wearing church choristers, the graphic scores provide an inclusive way of bringing this disparate group of performers together. Graphic scores also make sound-making tangible, explains Duncanson: they provide “something you can put your hands on and say ‘this is what we did’.”

Looking at Noizechoir’s graphic scores and listening to their recordings has taken me on a journey round northern England. Preston Bus Station is a place I’ve visited several times, in a town I know reasonably well. The following score was performed alongside a poem by Bruce Rafeek which evokes the history of the building, the spirit in which it was built and its place in the identity of the town. Together, they captured my imagination and made me want to revisit this seemingly ordinary place.

“We used the architecture as a score.”: ‘A Requiem for Preston Bus Station’, drawn by Marek Gabrysch, featuring the poet Bruce Rafeek, performed by Noizechoir and Bruce Rafeek at Preston Bus Station as part of They Eat Culture’s event Journey to the End of the World (2013)

Engines hiss. Buses reverse with insistent warning beeps. Doors open, half-close and open again. Footsteps run across the building and luggage drags across the rubber floor. Echoes. People bustle; confusion clangs in the distance, somewhere someone shouts and calls. Overlapping voices suggest multiple purposes: counter sales and travel advice vie with intrusive phone calls, tittle-tattle and the depersonalised, automated voice of the self-service supermarket checkout.

Preston, Poulton, Blackpool via Kirkham, Fleetwood, Ormskirk, Leyland, the Lakes. The destination announcements suggest home time, visits to family and friends or a day trip to the mountains or the sea.

It’s a familiar – if tired – place. This is the backdrop for hours spent hanging around waiting, worrying about delays and missed connections. But there’s also life and excitement here. It might have been built in a different era, but still the bus station has an essential function: it connects us with other places and people. It’s a social space.

The bus pulls in. The engine starts. The journey begins.

Lindisfarne is somewhere I have long wanted to visit. I have never managed to make the journey due to its remoteness and geographical distance from the North West, but Noizechoir’s work has made it feel a little bit closer.

“We researched the tidal patterns and migrating birds of Holy Island and played with the sea, the wind, traffic and people. The dynamics were based on the volume of the tide.”: ‘Tidalisle (Lindisfarne)’, designed by Marek Gabrsych and painted by Lindsay Duncanson, created for Perigrini Lindisfarne and performed by Noizechoir in Lindisfarne bird hide (2017)

The sea sends out feelers like wandering tentacles, then the tide rushes in with a sudden shock before beating a hasty retreat. It swells with a deep, ominous belly roar, a groan and a creak, as if it’s being heaved up from the deep, then ebbs away.

Again and again it comes, faster and more regular now, building up a rhythm as it’s pulled in and out. In the background an incantation is too indistinct to make out.

The waves lap and drag along the shore. Birds sigh and coo overhead. More and more join in, flitting around one another in the sky.

In the distance a bell tolls.

Footsteps, one in front of another. Slowly. A crossing.

The bell continues to call.

The sea retreats, to silence, the sound of the waves replaced by a whistling wind. The tinkling drip-dropping of rain grows more persistent.

Night falls.

The chanting grows, louder and louder, merging with the hiss of the sea. Then it vanishes, fading back until only a soft patter of water remains.

It begins again.

Originally published in the Fourdrinier, September 2020

See more of Noizechoir’s scores and listen to some of their performances

⬑

⬑