Bell tower façade relief [and truck], Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (c.1966)

A man, armed with a tube, is doodling giant-scale on a concrete wall. Dressed in white overalls he explains, from behind a protective helmet, that he is blasting the wall with grit, enthusiastically advocating the technique’s potential for widespread decorative use. The man is William Mitchell, artist, designer, innovator, inventor – and sometime television personality. Mitchell made an entertaining presenter and the programme demonstrating sandblasting was just one of the episodes of Tomorrow’s World he was asked to present because “I could talk at the same time and didn’t confuse people with art”. He remembers, “I got lots of letters from doctors saying I would die at a very young age as my lungs would be filled with dust and to stop what I was doing” – although at 86 he is still very much alive and opinionated.

In the 1960s and ’70s Mitchell, who had studied Industrial Design at the Royal College of Art, pioneered new techniques and materials, working with other professions such as architects, engineers and builders. In another edition of Tomorrow’s World, Mitchell balances on a plank of wood above a building site in Croydon, where he is installing a textured concrete wall in an office block. He explains: “There were not many people in my line of work who would go out on the roof with the builders. That was unusual. If it was now I would have had to wear protective clothing I couldn’t even get up the stairs in.” The most remarkable episode, though, is that in which he demonstrates a new technique he has come up with for advertising – an unrealised plan that have illuminated Manchester’s Piccadilly Gardens with a 350ft by 65ft sign comprising thousands of lightbulbs triggered by films and photoelectric cells. You can still see the holes on Piccadilly Plaza where the bulbs would have gone.

Planners across the UK – and as far afield as America and Hawaii – wanted a piece of Mitchell for their developments, and he undertook hundreds of public and private commissions. These range from the small, functional and unobtrusive – clocks in schools, motorway detailing – to the grand – the massive doors to Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (the design for which had to be signed-off by the Pope) and, later, the Egyptian Room at Harrods. Mitchell was so prolific he can’t remember the exact location and details of each artwork, but there are a several in some of Manchester’s most striking and iconic buildings – a bold fibreglass mural in the entrance to the CIS Tower, panels around the lift shaft in the snaking Gateway House on Piccadilly Approach and sculptured decoration covering the Humanities Building at the University of Manchester.

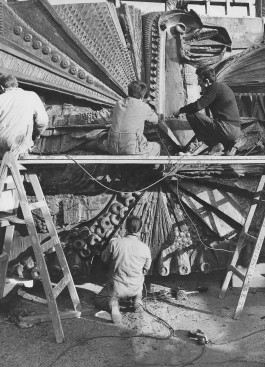

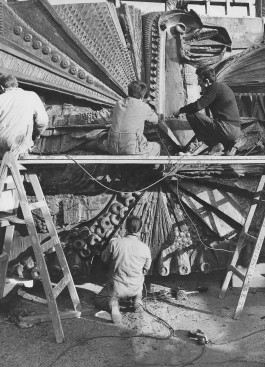

Mitchell [top right] and team, installing doors of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (c.1966)

Overview of Minut Men, University of Salford (1967)

Mitchell’s most publicly visible work in the city is his Minut Men, three giant concrete monsters outside the University of Salford. Mitchell had to set them on fire to get the plastic moulds off (something he notes would never be allowed today, especially so close to the main road!), and the figures are extraordinarily detailed, covered with patterns and inlaid with mosaic. He explains: “I wanted to do something with the material which was not indicative of trying to be something else. As it was new, let it be new. It had as much to do with the practicality and being outside. I also had to take into account, was it waterproof and was it vandal proof?”

Often, says Mitchell, his artworks used a “very, very involved process”, a challenge to himself to prove they were possible. He remembers: “It was almost an exercise in character building, the artworks were so hard to get to the finish of!” Another unusual use of materials can be seen in the epic mosaic, gleaming with objects such as bottle tops and textured by the addition of gravel, that climbs the full height of the staircase in the Piccadilly Hotel in Piccadilly Gardens. Made of bits of furniture and pianos set in resin, Mitchell wanted to show “there was still the possibility of doing hand craftwork” and says “there’s a richness to it”.

Mitchell finds public art to be a problematic concept: “One of the troubles of public art is the public are not asked whether or not they want it.” Yet you can tell Mitchell is proud of the artworks which people have taken to heart: he was pleased to hear of a fashion show being held in front of the Minut Men in Salford, and recounts that Salford students defended the figures from attack by rivals from Manchester University. He even tells a story of tenants taking it upon themselves to clean one of his artworks in a council block. Mitchell also considers his fantastical creatures for the water gardens in Harlow, Essex – modern day gargoyles for a new town – to be a success. Too often, he says, artworks of the period were “thought of as brooches to stick on the building”, whereas art needs to “give a sense of the international, community and place”. Harlow was different as “they were starting to put an infrastructure in, an environment”.

Mitchell would like to see a percentage for public art built into new developments today: “I think it’s appalling architects don’t consider art. It is so categorised today, art and architecture. There isn’t any interrelationship to my mind. At one time there was the possibility of an integrated art form but now you don’t get anything like that.”

He complains: “Every square inch in London is built up as far as ground level. Architecturally buildings take no notice of the pedestrian. Where the building hits the ground is more like the basement than a public thoroughfare.”

Mitchell’s sculptural relief panel being lifted into position

Some of Mitchell’s works have already been demolished, whereas others are in buildings that have fallen out of favour and face uncertain futures. He’s stoical about artworks being lost when buildings are knocked down, although he thinks it’s important that “some are kept to give an idea of what the time was like and the type of things you could do”. The social and historical significance of these remarkable artworks is now being reassessed. In Islington, London in 2008, one of Mitchell’s works for a school was the first mural of its kind to be listed in its own right, not in the context of the listing of the building to which it was attached. In a library in Kirkby near Liverpool too, a mural has recently been restored and reinstalled. It had languished in storage after the library, ironically, “took it down to be modern”. Those trying (unsuccessfully so far) to get the Turnpike Centre in Leigh listed, which, when it was opened in 1971 featured a new, open-plan library design, also highlight Mitchell’s distinctive concrete frieze on the front.

Mitchell still receives requests for commissions and is currently working on a book, which will be “part instruction book” (“always paint the concrete”, he insists) and “part adventure book”. There couldn’t be anything more appropriate for this brilliant artist. As he sums up his long career, “It has been an adventure!”

Originally published in The Modernist, Issue Nº 2 (Brilliant), September 2011

Images courtesy of William & Joy Mitchell

Bell tower façade relief [and truck], Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (c.1966)

A man, armed with a tube, is doodling giant-scale on a concrete wall. Dressed in white overalls he explains, from behind a protective helmet, that he is blasting the wall with grit, enthusiastically advocating the technique’s potential for widespread decorative use. The man is William Mitchell, artist, designer, innovator, inventor – and sometime television personality. Mitchell made an entertaining presenter and the programme demonstrating sandblasting was just one of the episodes of Tomorrow’s World he was asked to present because “I could talk at the same time and didn’t confuse people with art”. He remembers, “I got lots of letters from doctors saying I would die at a very young age as my lungs would be filled with dust and to stop what I was doing” – although at 86 he is still very much alive and opinionated.

In the 1960s and ’70s Mitchell, who had studied Industrial Design at the Royal College of Art, pioneered new techniques and materials, working with other professions such as architects, engineers and builders. In another edition of Tomorrow’s World, Mitchell balances on a plank of wood above a building site in Croydon, where he is installing a textured concrete wall in an office block. He explains: “There were not many people in my line of work who would go out on the roof with the builders. That was unusual. If it was now I would have had to wear protective clothing I couldn’t even get up the stairs in.” The most remarkable episode, though, is that in which he demonstrates a new technique he has come up with for advertising – an unrealised plan that have illuminated Manchester’s Piccadilly Gardens with a 350ft by 65ft sign comprising thousands of lightbulbs triggered by films and photoelectric cells. You can still see the holes on Piccadilly Plaza where the bulbs would have gone.

Planners across the UK – and as far afield as America and Hawaii – wanted a piece of Mitchell for their developments, and he undertook hundreds of public and private commissions. These range from the small, functional and unobtrusive – clocks in schools, motorway detailing – to the grand – the massive doors to Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (the design for which had to be signed-off by the Pope) and, later, the Egyptian Room at Harrods. Mitchell was so prolific he can’t remember the exact location and details of each artwork, but there are a several in some of Manchester’s most striking and iconic buildings – a bold fibreglass mural in the entrance to the CIS Tower, panels around the lift shaft in the snaking Gateway House on Piccadilly Approach and sculptured decoration covering the Humanities Building at the University of Manchester.

Mitchell [top right] and team, installing doors of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (c.1966)

Overview of Minut Men, University of Salford (1967)

Mitchell’s most publicly visible work in the city is his Minut Men, three giant concrete monsters outside the University of Salford. Mitchell had to set them on fire to get the plastic moulds off (something he notes would never be allowed today, especially so close to the main road!), and the figures are extraordinarily detailed, covered with patterns and inlaid with mosaic. He explains: “I wanted to do something with the material which was not indicative of trying to be something else. As it was new, let it be new. It had as much to do with the practicality and being outside. I also had to take into account, was it waterproof and was it vandal proof?”

Often, says Mitchell, his artworks used a “very, very involved process”, a challenge to himself to prove they were possible. He remembers: “It was almost an exercise in character building, the artworks were so hard to get to the finish of!” Another unusual use of materials can be seen in the epic mosaic, gleaming with objects such as bottle tops and textured by the addition of gravel, that climbs the full height of the staircase in the Piccadilly Hotel in Piccadilly Gardens. Made of bits of furniture and pianos set in resin, Mitchell wanted to show “there was still the possibility of doing hand craftwork” and says “there’s a richness to it”.

Mitchell finds public art to be a problematic concept: “One of the troubles of public art is the public are not asked whether or not they want it.” Yet you can tell Mitchell is proud of the artworks which people have taken to heart: he was pleased to hear of a fashion show being held in front of the Minut Men in Salford, and recounts that Salford students defended the figures from attack by rivals from Manchester University. He even tells a story of tenants taking it upon themselves to clean one of his artworks in a council block. Mitchell also considers his fantastical creatures for the water gardens in Harlow, Essex – modern day gargoyles for a new town – to be a success. Too often, he says, artworks of the period were “thought of as brooches to stick on the building”, whereas art needs to “give a sense of the international, community and place”. Harlow was different as “they were starting to put an infrastructure in, an environment”.

Mitchell would like to see a percentage for public art built into new developments today: “I think it’s appalling architects don’t consider art. It is so categorised today, art and architecture. There isn’t any interrelationship to my mind. At one time there was the possibility of an integrated art form but now you don’t get anything like that.”

He complains: “Every square inch in London is built up as far as ground level. Architecturally buildings take no notice of the pedestrian. Where the building hits the ground is more like the basement than a public thoroughfare.”

Mitchell’s sculptural relief panel being lifted into position

Some of Mitchell’s works have already been demolished, whereas others are in buildings that have fallen out of favour and face uncertain futures. He’s stoical about artworks being lost when buildings are knocked down, although he thinks it’s important that “some are kept to give an idea of what the time was like and the type of things you could do”. The social and historical significance of these remarkable artworks is now being reassessed. In Islington, London in 2008, one of Mitchell’s works for a school was the first mural of its kind to be listed in its own right, not in the context of the listing of the building to which it was attached. In a library in Kirkby near Liverpool too, a mural has recently been restored and reinstalled. It had languished in storage after the library, ironically, “took it down to be modern”. Those trying (unsuccessfully so far) to get the Turnpike Centre in Leigh listed, which, when it was opened in 1971 featured a new, open-plan library design, also highlight Mitchell’s distinctive concrete frieze on the front.

Mitchell still receives requests for commissions and is currently working on a book, which will be “part instruction book” (“always paint the concrete”, he insists) and “part adventure book”. There couldn’t be anything more appropriate for this brilliant artist. As he sums up his long career, “It has been an adventure!”

Originally published in The Modernist, Issue Nº 2 (Brilliant), September 2011

Images courtesy of William & Joy Mitchell

⬑

⬑