Written by Juliet Kinchin / Aidan O’Connor, published by The Museum of Modern Art, New York (2012)

From slaving in factories in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to becoming a target market for consumer fashions in the late twentieth century, the child’s place and value in society has undergone a remarkable shift over the last 100 years. Despite this, argue the authors of a new book produced by the Museum of Modern Art in New York to accompany last year’s major exhibition The Century of the Child: Growing by Design 1900 – 2000, their significance in design history has been underestimated.

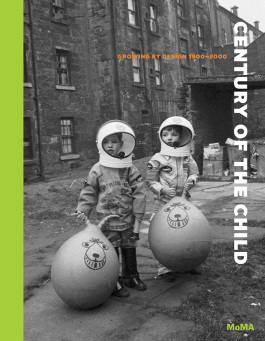

Century of the Child borrows its title from the 1900 manifesto of the same name by Swedish design reformer and social theorist Ellen Key, offering a lavish accompaniment to an exhibition that examined everything from avant-garde toys, furniture and playgrounds to kindergartens, schools and pedagogies. Quotes from Key’s text recur throughout the book, and the title is used as a starting point to explore new attitudes towards children brought about by the social upheaval of the twentieth century, including slum clearance, world war and regeneration, the prominence of the space race in the popular imagination and the rise of mass media such as television. Pictures of playthings and playrooms are illuminated by original designs and archive photographs, alongside essays exploring key figures, movements and moments – primarily in the United States and Europe, but with occasional forays into Latin America, Japan and colonial West Africa.

Ladislav Sutnar, Prototype for Build the Town Building Blocks (1940–1943), The Museum of Modern Art, New York

As well as looking at the ways in which changing perspectives on childhood were manifested in specific design objects, buildings and places, among the most interesting chapters are those which consider the political implications of this new focus on the child. It’s hard begrudge the high ideals of Utopian Modernist planners who aimed to ensure that the next generation of citizens grew up in healthy environments with access to light, space and air, but more problematic is the idea of the child as a ‘clean slate’ ready to be filled with ideas: state control over children’s lives could lead to indoctrination, for example through the fascist youth groups of inter-war Italy and Germany. The book shows examples of how the image of children can be manipulated, both as political propaganda and through appropriation in advertising campaigns. Furthermore, despite the aims of those behind it, access to innovative, good quality design was often restricted to those with either money or cultural capital due to the lack of commercial potential for production on a mass-market scale. And it’s hard to forget the situation of children in developing and war-torn countries today, experiencing a childhood – or lack of – a world away from the lives of their peers in the West, in some cases making toys for the entertainment of other children.

As we progress further into the twenty-first century, the gap between child and adult life is diminishing, and gadgets such as smartphones, e-readers and laptops are shared by adults and children alike. Is it that children are growing up fast nowadays – or, are we all closer to children now?

Originally published in The Modernist, Issue Nº 7 (Capital), March 2013

Images courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Written by Juliet Kinchin / Aidan O’Connor, published by The Museum of Modern Art, New York (2012)

From slaving in factories in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to becoming a target market for consumer fashions in the late twentieth century, the child’s place and value in society has undergone a remarkable shift over the last 100 years. Despite this, argue the authors of a new book produced by the Museum of Modern Art in New York to accompany last year’s major exhibition The Century of the Child: Growing by Design 1900 – 2000, their significance in design history has been underestimated.

Century of the Child borrows its title from the 1900 manifesto of the same name by Swedish design reformer and social theorist Ellen Key, offering a lavish accompaniment to an exhibition that examined everything from avant-garde toys, furniture and playgrounds to kindergartens, schools and pedagogies. Quotes from Key’s text recur throughout the book, and the title is used as a starting point to explore new attitudes towards children brought about by the social upheaval of the twentieth century, including slum clearance, world war and regeneration, the prominence of the space race in the popular imagination and the rise of mass media such as television. Pictures of playthings and playrooms are illuminated by original designs and archive photographs, alongside essays exploring key figures, movements and moments – primarily in the United States and Europe, but with occasional forays into Latin America, Japan and colonial West Africa.

Ladislav Sutnar, Prototype for Build the Town Building Blocks (1940–1943), The Museum of Modern Art, New York

As well as looking at the ways in which changing perspectives on childhood were manifested in specific design objects, buildings and places, among the most interesting chapters are those which consider the political implications of this new focus on the child. It’s hard begrudge the high ideals of Utopian Modernist planners who aimed to ensure that the next generation of citizens grew up in healthy environments with access to light, space and air, but more problematic is the idea of the child as a ‘clean slate’ ready to be filled with ideas: state control over children’s lives could lead to indoctrination, for example through the fascist youth groups of inter-war Italy and Germany. The book shows examples of how the image of children can be manipulated, both as political propaganda and through appropriation in advertising campaigns. Furthermore, despite the aims of those behind it, access to innovative, good quality design was often restricted to those with either money or cultural capital due to the lack of commercial potential for production on a mass-market scale. And it’s hard to forget the situation of children in developing and war-torn countries today, experiencing a childhood – or lack of – a world away from the lives of their peers in the West, in some cases making toys for the entertainment of other children.

As we progress further into the twenty-first century, the gap between child and adult life is diminishing, and gadgets such as smartphones, e-readers and laptops are shared by adults and children alike. Is it that children are growing up fast nowadays – or, are we all closer to children now?

Originally published in The Modernist, Issue Nº 7 (Capital), March 2013

Images courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York

⬑

⬑