I first became aware of the work of Jane and Louise Wilson at the Whitworth Art Gallery some years ago, when their multi-screen video installation Monument was on display. Part of the Whitworth’s permanent collection, the video shows schoolboys clambering over Victor Pasmore’s brutalist, concrete Apollo Pavilion in Peterlee, County Durham, exploring the building as a giant climbing frame. Erected at the centre of the new town as an expression of the optimism and innovation of the space race era, the structure fell into disrepair and disfavour before being re-evaluated and repaired in recent years.

Now, the Whitworth is showing a recent project by Jane and Louise Wilson, similarly drawing on the optimism once embodied by the architecture and innovations of the twentieth century, but this time showing where it all went wrong. For Atomgrad (Nature Abhors a Vacuum), the Wilsons focus on a new town built for the workers of Chernobyl, which has been abandoned to decay and dereliction, and document how the bright future promised by nuclear power turned out to be dangerous and unpredictable.

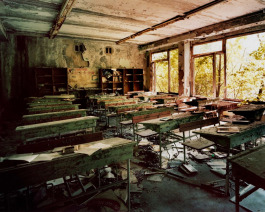

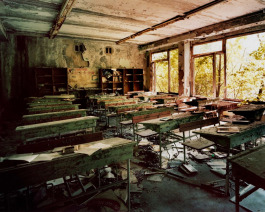

The Wilsons were commissioned to create a project about Chernobyl to mark the 25th anniversary of the nuclear disaster. On April 26 1986, a reactor at the power plant exploded, scattering radioactive matter into the environment. Priyapat, a town built in the Ukraine to house 50,000 Chernobyl workers, was in the exclusion zone, and its residents were evacuated, never to return. In Pripyat, everything its inhabitants could need was planned for – schools, healthcare, entertainment, recreation, and the Wilsons have captured a crumbling cinema hall, a library in disarray with books tumbled from the shelves, a dormitory vacated with beds still unmade, rows of desks in a classroom forever out to recess and an empty swimming pool flooded with light, overlooking a verdant forest as if part of a secluded holiday retreat. Into each image has crept a measuring stick, scarcely noticeable and stripped of its function; wrapped around a doorframe, teetering at the edge of a diving board, marking the edge of a door. Physical recreations of these measuring sticks recur throughout the show at the Whitworth as sculptural forms yet, unlike the measuring sticks in the images, they dominate the exhibition spaces, forming a barrier across a corner of the room containing the photographs, and stretching intrusively to the ceiling.

Accompanying the still, eerie beauty of the photographs, which are devoid of people, is The Toxic Camera, a poignant reminder of the human cost of the disaster. The title refers to the camera of Vladmir Shevchenko, a film-maker allowed access to the power plant in the aftermath of the explosion. Shevchenko unwittingly captured the code-like beeping of radiation on film, and the exposure was to kill him; the Wilsons have placed a bronze replica of his camera, recast as a lethal weapon, on an austere concrete pedestal. In the film, members of Shevchenko’s crew, their faces thoughtful and sad, reflect on their colleague and children play listlessly with an electric fence, capturing the repercussions of the disaster for each generation to come.

Whereas The Toxic Camera amplifies sound and image (in one of the most effective moments an apple, made inedible by radiation, falls with a ‘thwack’ to a floor already covered in over-ripe apples), the silence of Shevchenko’s documentary Chernobyl: A Chronicle of Difficult Weeks, which plays nearby, is both ominous and compelling. A montage comprising action footage of power plant workers and the emergency services, aerial footage of the affected area and news-bulletin style responses from those in power gives a heroic visual account of the rescue attempt.

Elsewhere in the exhibition another recent film by the Wilsons, Face Scripting: What Did the Building See, plays out in today’s anonymous, familiar, controlled spaces of hotel lobbies, shopping malls and airport security checks. The murder of Hamas operative Mahmoud Al-Mabhouh in Dubai in 2010 is narrated through CCTV footage, mediated by explanatory subtitles. The screen showing CCTV footage faces a film by the Wilsons which simulates the anonymous hotel room in which the murder took place through banal close-ups of details such as the room phone and the carpet. With one film facing the other, requiring the viewer to always have their back to one of the screens, it is impossible to reconcile the two accounts of the narrative at once. In reality, Al-Mabhouh’s hotel room was the only space in the story free from CCTV, showing the impossibility of seeking to see everywhere and everything at once, even with today’s technical innovations.

This reiterates the message of the measuring sticks which recur throughout the show, serving as a reminder of the limits of human control. Society can seek to harness nuclear power, send men into space, and record citizens’ every move, but the world is not always safe, measurable and planned for; there are some eventualities which cannot be controlled.

Originally published in Corridor8, January 2013

I first became aware of the work of Jane and Louise Wilson at the Whitworth Art Gallery some years ago, when their multi-screen video installation Monument was on display. Part of the Whitworth’s permanent collection, the video shows schoolboys clambering over Victor Pasmore’s brutalist, concrete Apollo Pavilion in Peterlee, County Durham, exploring the building as a giant climbing frame. Erected at the centre of the new town as an expression of the optimism and innovation of the space race era, the structure fell into disrepair and disfavour before being re-evaluated and repaired in recent years.

Now, the Whitworth is showing a recent project by Jane and Louise Wilson, similarly drawing on the optimism once embodied by the architecture and innovations of the twentieth century, but this time showing where it all went wrong. For Atomgrad (Nature Abhors a Vacuum), the Wilsons focus on a new town built for the workers of Chernobyl, which has been abandoned to decay and dereliction, and document how the bright future promised by nuclear power turned out to be dangerous and unpredictable.

The Wilsons were commissioned to create a project about Chernobyl to mark the 25th anniversary of the nuclear disaster. On April 26 1986, a reactor at the power plant exploded, scattering radioactive matter into the environment. Priyapat, a town built in the Ukraine to house 50,000 Chernobyl workers, was in the exclusion zone, and its residents were evacuated, never to return. In Pripyat, everything its inhabitants could need was planned for – schools, healthcare, entertainment, recreation, and the Wilsons have captured a crumbling cinema hall, a library in disarray with books tumbled from the shelves, a dormitory vacated with beds still unmade, rows of desks in a classroom forever out to recess and an empty swimming pool flooded with light, overlooking a verdant forest as if part of a secluded holiday retreat. Into each image has crept a measuring stick, scarcely noticeable and stripped of its function; wrapped around a doorframe, teetering at the edge of a diving board, marking the edge of a door. Physical recreations of these measuring sticks recur throughout the show at the Whitworth as sculptural forms yet, unlike the measuring sticks in the images, they dominate the exhibition spaces, forming a barrier across a corner of the room containing the photographs, and stretching intrusively to the ceiling.

Accompanying the still, eerie beauty of the photographs, which are devoid of people, is The Toxic Camera, a poignant reminder of the human cost of the disaster. The title refers to the camera of Vladmir Shevchenko, a film-maker allowed access to the power plant in the aftermath of the explosion. Shevchenko unwittingly captured the code-like beeping of radiation on film, and the exposure was to kill him; the Wilsons have placed a bronze replica of his camera, recast as a lethal weapon, on an austere concrete pedestal. In the film, members of Shevchenko’s crew, their faces thoughtful and sad, reflect on their colleague and children play listlessly with an electric fence, capturing the repercussions of the disaster for each generation to come.

Whereas The Toxic Camera amplifies sound and image (in one of the most effective moments an apple, made inedible by radiation, falls with a ‘thwack’ to a floor already covered in over-ripe apples), the silence of Shevchenko’s documentary Chernobyl: A Chronicle of Difficult Weeks, which plays nearby, is both ominous and compelling. A montage comprising action footage of power plant workers and the emergency services, aerial footage of the affected area and news-bulletin style responses from those in power gives a heroic visual account of the rescue attempt.

Elsewhere in the exhibition another recent film by the Wilsons, Face Scripting: What Did the Building See, plays out in today’s anonymous, familiar, controlled spaces of hotel lobbies, shopping malls and airport security checks. The murder of Hamas operative Mahmoud Al-Mabhouh in Dubai in 2010 is narrated through CCTV footage, mediated by explanatory subtitles. The screen showing CCTV footage faces a film by the Wilsons which simulates the anonymous hotel room in which the murder took place through banal close-ups of details such as the room phone and the carpet. With one film facing the other, requiring the viewer to always have their back to one of the screens, it is impossible to reconcile the two accounts of the narrative at once. In reality, Al-Mabhouh’s hotel room was the only space in the story free from CCTV, showing the impossibility of seeking to see everywhere and everything at once, even with today’s technical innovations.

This reiterates the message of the measuring sticks which recur throughout the show, serving as a reminder of the limits of human control. Society can seek to harness nuclear power, send men into space, and record citizens’ every move, but the world is not always safe, measurable and planned for; there are some eventualities which cannot be controlled.

Originally published in Corridor8, January 2013

⬑

⬑