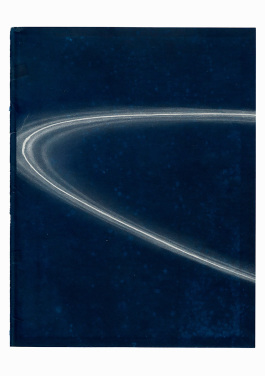

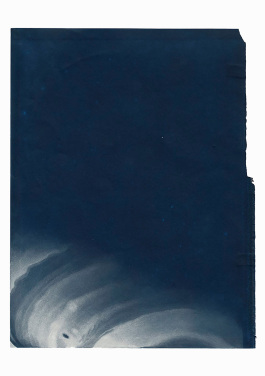

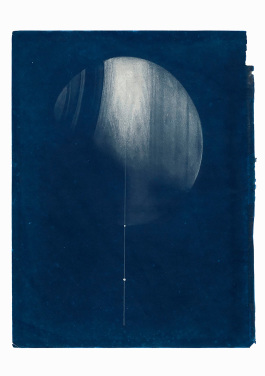

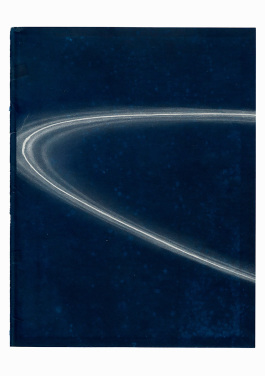

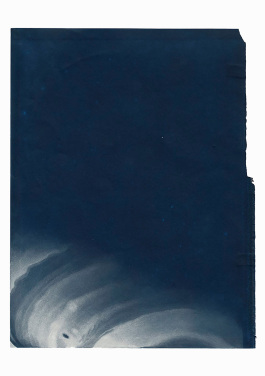

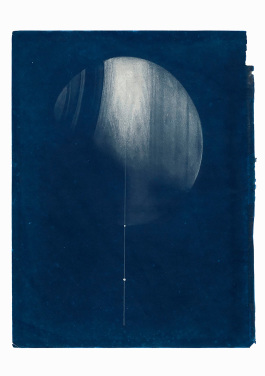

Hondartza Fraga, Saturn Incognito, inverted digital print (2019)

Hondartza Fraga, Saturn Incognito, inverted digital print (2019)

Space and our relationship with it loomed large in the public consciousness in 2019, following the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landings. Space travel demonstrates human and technological capabilities yet reminds us of our limits. Because most people are unlikely to visit, images and testimonies from space can be so distanced from our lives as to feel almost unreal.

Spanish-born, Yorkshire-based artist Hondartza Fraga is interested our relationship with scientific images of space and the ways in which artistic responses to these might give us new meanings. “I’ve always been interested in space,” she explains. “I’m interested in the places we can’t access very easily, so we need images of them, such as deep space, deep sea and the poles. These are places we look at from afar. Space is the ultimate place we cannot inhabit – but we can see it with the help of technology.”

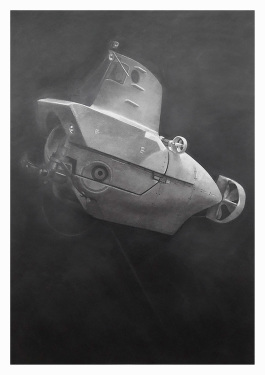

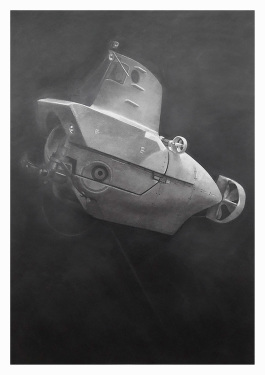

Working in a photorealist style that she says is “very open about its relationship to photography,” Fraga’s drawings are characterised by meticulous attention to detail. Her eye has previously been drawn to mechanical aids for advancing human understanding: in 2016 she drew a globe per day, observing the subtle similarities and differences in an once commonplace yet now archaic method for mapping and navigating the world. During a residency at Jodrell Bank Observatory, she created a series of hybrid machine-natural forms, juxtaposing the high-tech Lovell telescope with its incongruous setting in the Cheshire countryside. Specimens (2018 – ongoing) is a series of drawings of objects that “carry humans to remote spaces.” One image depicts a submersible, which travels to the deepest part of the ocean, whilst another shows the craft that took astronauts to the moon, “the furthest we’ve physically been.”

Hondartza Fraga, Specimens II, graphite on paper (2018)

At the moment she is working with more abstract material: a remarkable set of almost 400,000 ‘raw images’ of Saturn beamed back by the Cassini voyager between 2004 and 2017, all of which are openly available online via the NASA website.

“If you ask what Saturn looks like, anyone can describe it on a basic level,” Fraga says. However, seen by the naked eye it is “just a dot, like another star – we need technology to see it.”

The Cassini images have been used by NASA to build a composite picture of Saturn. From these fragments has emerged what Fraga describes as a “seamless mosaic,” presented as an official product of scientific truth. This is the type of image we might see in our mind when picturing the planet: a perfect sphere encircled with rings in the centre of a dark background.

In their original form, by contrast, the raw images of Saturn are in black and white and low resolution. “The Cassini images are not sublime – they are very small and intimate,” observes Fraga. “They are almost the most contemporary images you can find in terms of astronomy, but they look old and archaic, like early cinema.”

As we talk in her studio in Leeds, Fraga takes me through the Cassini webpage. At the bottom of each raw image is the phrase: ‘This image has not been validated or calibrated’. Fraga explains that this means “these images are in between. They have not been processed or given scientific truth yet, so they are not fully scientific.”

Of these thousands of images, Fraga had about 200 printed onto photographic paper so she could “hold them in her hand.” As she lays them out in front of us, she explains that she selected the more abstract images. “I became interested in the errors in the images,” she explains. “Some of them are nothing but errors.” The Cassini images were taken by a machine, so there was no viewfinder. Some are pixelated or include blemishes such as dust particles and cosmic rays, whilst others are marked with bands, black lines and rings. Other imperfections are due to camera error, such as glare or exposure time which has left a blur in the background. Because filters such as UV were used, they “already look unnatural” to Fraga. Sometimes, she has to show me where Saturn is, as it’s on the edge of the image and not easily identifiable.

Fraga has been working with these images since 2009, when she turned them into an animation. In 2017 – the year the mission finished and the set of photographs was completed – she started a practice-based PhD at the University of Leeds, using the Cassini images as a starting point. Around us on the walls of her studio these images reappear as experiments in medium and form, complicating the relationship between scientific and artistic documentation, and analogue and digital transmission.

Just as the Cassini images have been heavily edited to produce the final result, Fraga has subjected her own response to layers of processing. Among the results are a series of blue-tinged prints resembling vintage cyanotypes. To create them, Fraga drew the inversion of the original Cassini images, thereby “giving them a negative” and imbuing them with the attributes of an analogue image. “Digital photos are not real for some people, as they have not gone through the process of light hitting the plate,” explains Fraga. “Some people feel that analogue has a special connection with reality because it’s a snapshot of one moment.”

Hondartza Fraga, Saturn Incognito, inverted digital print (2019)

The images were drawn onto antique paper bought on eBay, gaining further blips as they were transcribed. Often coming from sources such as the end pages of music books, not all the paper was of the same quality. Some was thick and some was thin, and there were subtle differences in colour. These inconsistencies became a part of the drawings, which were then scanned and transformed again, into digital prints.

Permeating all of Fraga’s work is the concept of melancholy, which she is using as a loose framework to reflect on drawing. As well as the nostalgic and melancholic qualities of old photographs and collections, Fraga is interested in what this might look like not just as an emotion, but as a visual quality.

Photorealism can, itself, be seen as melancholy, she points out, as an activity that is labour-intensive and potentially futile. “What’s the point of photorealist drawing?” she asks. “What’s the point of reproducing something exactly? Photorealism is trying to display skill by hiding its own mark, but it’s never exact. What are the errors in the drawing?” To my mind, Fraga’s drawings suggest it’s these errors that open up space for the artist. The gaps in what we know leave room to explore and communicate new interpretations of reality.

Originally published in the Fourdrinier, October 2019

Hondartza Fraga, Saturn Incognito, inverted digital print (2019)

Hondartza Fraga, Saturn Incognito, inverted digital print (2019)

Space and our relationship with it loomed large in the public consciousness in 2019, following the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landings. Space travel demonstrates human and technological capabilities yet reminds us of our limits. Because most people are unlikely to visit, images and testimonies from space can be so distanced from our lives as to feel almost unreal.

Spanish-born, Yorkshire-based artist Hondartza Fraga is interested our relationship with scientific images of space and the ways in which artistic responses to these might give us new meanings. “I’ve always been interested in space,” she explains. “I’m interested in the places we can’t access very easily, so we need images of them, such as deep space, deep sea and the poles. These are places we look at from afar. Space is the ultimate place we cannot inhabit – but we can see it with the help of technology.”

Working in a photorealist style that she says is “very open about its relationship to photography,” Fraga’s drawings are characterised by meticulous attention to detail. Her eye has previously been drawn to mechanical aids for advancing human understanding: in 2016 she drew a globe per day, observing the subtle similarities and differences in an once commonplace yet now archaic method for mapping and navigating the world. During a residency at Jodrell Bank Observatory, she created a series of hybrid machine-natural forms, juxtaposing the high-tech Lovell telescope with its incongruous setting in the Cheshire countryside. Specimens (2018 – ongoing) is a series of drawings of objects that “carry humans to remote spaces.” One image depicts a submersible, which travels to the deepest part of the ocean, whilst another shows the craft that took astronauts to the moon, “the furthest we’ve physically been.”

Hondartza Fraga, Specimens II, graphite on paper (2018)

At the moment she is working with more abstract material: a remarkable set of almost 400,000 ‘raw images’ of Saturn beamed back by the Cassini voyager between 2004 and 2017, all of which are openly available online via the NASA website.

“If you ask what Saturn looks like, anyone can describe it on a basic level,” Fraga says. However, seen by the naked eye it is “just a dot, like another star – we need technology to see it.”

The Cassini images have been used by NASA to build a composite picture of Saturn. From these fragments has emerged what Fraga describes as a “seamless mosaic,” presented as an official product of scientific truth. This is the type of image we might see in our mind when picturing the planet: a perfect sphere encircled with rings in the centre of a dark background.

In their original form, by contrast, the raw images of Saturn are in black and white and low resolution. “The Cassini images are not sublime – they are very small and intimate,” observes Fraga. “They are almost the most contemporary images you can find in terms of astronomy, but they look old and archaic, like early cinema.”

As we talk in her studio in Leeds, Fraga takes me through the Cassini webpage. At the bottom of each raw image is the phrase: ‘This image has not been validated or calibrated’. Fraga explains that this means “these images are in between. They have not been processed or given scientific truth yet, so they are not fully scientific.”

Of these thousands of images, Fraga had about 200 printed onto photographic paper so she could “hold them in her hand.” As she lays them out in front of us, she explains that she selected the more abstract images. “I became interested in the errors in the images,” she explains. “Some of them are nothing but errors.” The Cassini images were taken by a machine, so there was no viewfinder. Some are pixelated or include blemishes such as dust particles and cosmic rays, whilst others are marked with bands, black lines and rings. Other imperfections are due to camera error, such as glare or exposure time which has left a blur in the background. Because filters such as UV were used, they “already look unnatural” to Fraga. Sometimes, she has to show me where Saturn is, as it’s on the edge of the image and not easily identifiable.

Fraga has been working with these images since 2009, when she turned them into an animation. In 2017 – the year the mission finished and the set of photographs was completed – she started a practice-based PhD at the University of Leeds, using the Cassini images as a starting point. Around us on the walls of her studio these images reappear as experiments in medium and form, complicating the relationship between scientific and artistic documentation, and analogue and digital transmission.

Just as the Cassini images have been heavily edited to produce the final result, Fraga has subjected her own response to layers of processing. Among the results are a series of blue-tinged prints resembling vintage cyanotypes. To create them, Fraga drew the inversion of the original Cassini images, thereby “giving them a negative” and imbuing them with the attributes of an analogue image. “Digital photos are not real for some people, as they have not gone through the process of light hitting the plate,” explains Fraga. “Some people feel that analogue has a special connection with reality because it’s a snapshot of one moment.”

Hondartza Fraga, Saturn Incognito, inverted digital print (2019)

The images were drawn onto antique paper bought on eBay, gaining further blips as they were transcribed. Often coming from sources such as the end pages of music books, not all the paper was of the same quality. Some was thick and some was thin, and there were subtle differences in colour. These inconsistencies became a part of the drawings, which were then scanned and transformed again, into digital prints.

Permeating all of Fraga’s work is the concept of melancholy, which she is using as a loose framework to reflect on drawing. As well as the nostalgic and melancholic qualities of old photographs and collections, Fraga is interested in what this might look like not just as an emotion, but as a visual quality.

Photorealism can, itself, be seen as melancholy, she points out, as an activity that is labour-intensive and potentially futile. “What’s the point of photorealist drawing?” she asks. “What’s the point of reproducing something exactly? Photorealism is trying to display skill by hiding its own mark, but it’s never exact. What are the errors in the drawing?” To my mind, Fraga’s drawings suggest it’s these errors that open up space for the artist. The gaps in what we know leave room to explore and communicate new interpretations of reality.

Originally published in the Fourdrinier, October 2019

⬑

⬑